Sri Lanka’s new irrigation pipes won’t automatically drought-proof your greenhouse

Most Sri Lankan growers see “more water” and think the problem is solved. With the Asian Development Bank (ADB) backing new modern pipe distribution network (PDN) systems to ease water shortages, it is tempting to just tap the nearest pipe and scale up your hydroponics or greenhouse immediately.

That is how you end up with blocked permits, fines for illegal discharge, or basil that mysteriously underperforms despite expensive nutrients.

This guide walks you through, step by step, how to connect to Sri Lanka’s new PDN-style supply in a way that is:

- Legal (permits, approvals, agencies you actually deal with)

- Technically sound (pressure, filtration, EC, hardness, alkalinity, pH control)

- Compliant on waste and RO brine (so the Central Environmental Authority and local councils are not on your back)

- Optimised for Kratky, DWC, NFT and greenhouse systems in a drought-prone climate

The ADB-financed program is specifically aimed at modernizing irrigation and pipe networks to reduce losses and support climate-resilient agriculture in Sri Lanka, giving farmers more reliable, pressurized water supplies for high-value crops and protected cultivation as reported in this ADB project update. If you set up your connection and treatment correctly now, you lock in stable, drought-resistant yields for the next decade.

1. Common mistakes Sri Lankan CEA growers make with new PDN water

1.1 Treating PDN water as “ready to use” for hydroponics

Pressurized does not mean hydroponic-ready. Water delivered through upgraded irrigation and rural schemes will usually be designed for surface irrigation or domestic use, not for recirculating root zones in DWC or NFT.

Typical problems when growers skip conditioning:

- Excess alkalinity and hardness from groundwater or mixed sources, driving pH up and precipitating calcium phosphate in lines and drippers.

- Highly variable EC depending on season and upstream blending.

- Residual chlorine/chloramine from schemes that integrate treated potable water, which can damage roots and beneficial microbes.

1.2 Connecting without the right permits or approvals

Sri Lanka’s water governance is fragmented: the Irrigation Department, National Water Resources Authority (proposed NWRA in the draft Water Resources law), National Water Supply and Drainage Board (NWSDB), Provincial Councils and local authorities all play roles in supply and discharge, as described in this review of Sri Lanka’s water governance and this FAO case study.

Two mistakes show up repeatedly when commercial hydroponic and greenhouse operators try to hook into new pipe networks:

- Informal tapping of small irrigation laterals without documented allocation from the local Irrigation Department office.

- Skipping wastewater / brine discharge permits where operations are within local authority or Pradeshiya Sabha jurisdictions.

1.3 Ignoring RO brine management

Many Sri Lankan growers use reverse osmosis to strip hardness and contaminants out of boreholes and piped water before mixing hydroponic nutrients. RO solves one problem and creates another: brine.

Studies on rural RO plants in Sri Lanka have already flagged unplanned brine removal as a key issue, with low recovery rates and poor disposal threatening soil and water salinisation, as noted in this groundwater and RO review.

Dumping RO concentrate into drains, canals or on bare ground near your greenhouse is the fastest way to get complaints from neighbouring paddy farmers.

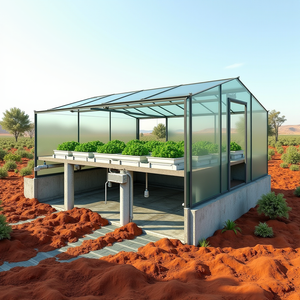

1.4 Designing greenhouses like they still rely on canal rotations

The whole point of PDN upgrades is to deliver water on demand instead of in rigid rotation schedules. But many CEA builds still behave as if water will arrive in big, irregular bursts:

- Oversized open reservoirs with massive evaporation losses.

- No buffering tanks between PDN intake and hydroponic mixing tanks.

- No metering at the point of use, so there is no baseline for water efficiency or negotiation of allocations.

When drought hits and allocations tighten, these systems are usually the first to struggle.

2. Why these mistakes keep happening in the PDN context

2.1 The “drinking water is good enough” assumption

NWSDB’s mandate is to provide safe drinking water and sanitation, not perfectly tuned hydroponic feed water. According to the NWSDB overview, the Board operates major water supply schemes and enforces potable standards.

Those standards allow levels of hardness and alkalinity that are completely acceptable for households but problematic for precise nutrient management. A supply that is “safe to drink” can still:

- Push your unadjusted nutrient solution above 2.5 mS/cm before you even add salts.

- Force you to dump reservoirs frequently because pH keeps drifting above 7.0.

PDN upgrades will stabilise flow and pressure, but source blending, hardness and alkalinity profiles will still be site-specific.

2.2 Complex but real permit architecture

Under the proposed water rights administration framework, the National Water Resources Authority (NWRA) is expected to handle water use entitlements and wastewater discharge permits at basin level, to coordinate allocations and discharges as highlighted in the FAO Sri Lanka case study. At the same time:

- The Irrigation Department controls major irrigation schemes, many of which are being modernised with new PDN-style distribution.

- NWSDB manages potable and many rural piped schemes.

- Local authorities and the Central Environmental Authority (CEA) oversee effluent and environmental approvals.

Because CEA and basin-level water rights enforcement are still evolving, many growers have historically operated “in the grey”. As PDN systems arrive with ADB funding and stricter performance targets, enforcement and metering typically follow.

2.3 RO as a universal hammer

RO has become the default answer to any water quality problem in Sri Lanka. The MDPI groundwater review points out that many rural RO plants achieve over 95% removal of problematic constituents but with low recovery, often around 46%, and problematic brine removal practices documented here.

In hydroponics, that mindset leads to:

- Oversized RO systems running at low recovery, wasting water and power.

- Ignored brine streams that quietly damage nearby soils or drains.

- Running 100% RO water with no remineralisation plan, which can destabilise pH and micronutrient uptake in Kratky and DWC.

2.4 Greenhouses designed without water as a monitored input

Traditional irrigation culture is volume- and season-focused: “Did we get our turn?” CEA needs a different mindset: “How many litres per kilogram of output did we use?”

The ADB’s PDN initiative specifically aims to reduce conveyance losses and increase water productivity at farm level, not just deliver more raw volume, as outlined in this project note. Without meters and storage design that reflects this, growers miss opportunities to prove efficiency and negotiate fair allocations.

3. How to fix it: step-by-step connection and conditioning for Sri Lankan PDN water

3.1 Map your agencies and permits before you lay a single pipe

Before buying pumps or filters, answer these questions:

- Where is your water coming from?

- Major irrigation scheme PDN: Start with the local office of the Irrigation Department or project management unit. Ask if the scheme has specific CEA or ADB safeguard conditions tied to water use and drainage.

- NWSDB rural/urban piped supply: Contact the regional support centre of NWSDB, which operates across Sri Lanka’s provinces as noted in this NWSDB profile. You will need a commercial or bulk connection.

- Private borehole plus PDN backup: You may need a water use entitlement from the emerging NWRA framework, particularly if you plan high abstraction.

- Where is your wastewater going?

- Closed-loop hydroponics has minimal discharge if managed well, but you still need a plan for tank cleaning, filter backwash and RO brine.

- Any discharge to drains, irrigation canals or natural water bodies can trigger permit requirements under CEA and local council rules, similar to the way other countries regulate hydroponic effluent as explained in this regulatory overview.

Practical tip: Put everything in writing. A one-page concept note with your location, expected daily demand (m³/day), crops and discharge plan makes it much easier to get clear answers.

3.2 Design your PDN intake for hydroponic stability, not just flow

Your objective is to turn a variable-pressure PDN into a stable, predictable supply that feeds your Kratky, DWC, NFT and drip lines.

Core layout:

- PDN connection point with an approved meter, isolation valve and pressure-reducing valve (if pressures exceed your plumbing ratings).

- Raw water buffer tank (covered) sized for at least 1–2 days of peak use.

- Pre-filtration rack between buffer and hydroponic mixing tanks.

- Nutrient mixing / control tanks (one per crop type is ideal).

Minimum filtration for PDN water:

- Coarse screen or disc filter (80–120 mesh) to protect valves and emitters.

- Cartridge or multimedia filter if turbidity fluctuates.

- Activated carbon if you are on an NWSDB supply with residual chlorine/chloramine.

3.3 Test the water properly before committing to RO

Run a basic profile on your PDN source and any borehole you plan to blend:

- EC (µS/cm or mS/cm)

- pH

- Total hardness (CaCO₃ mg/L)

- Alkalinity (CaCO₃ mg/L)

- Sodium (Na), chloride (Cl), bicarbonate (HCO₃) if you can afford a lab panel

Once you have that, you can decide:

- If EC is below 0.4 mS/cm and alkalinity below 60 mg/L CaCO₃, you may be able to run without RO for leafy greens and herbs, adjusting pH with acid as needed.

- If EC is high (above 0.8–1.0 mS/cm) and alkalinity is 120–200 mg/L CaCO₃ or more, a blended RO setup (for example 50% RO, 50% raw) is often better than running 100% RO, especially for fruiting crops.

Design your nutrient recipes so that the final solution EC is within crop norms (1.2–1.8 mS/cm for most leafy greens, 2.0–3.0 mS/cm for tomatoes and capsicum) and the pH stays between 5.5 and 6.5, aligning with standard hydroponic practice discussed in many nutrient management guides.

3.4 Brine management that won’t get you in trouble

For a commercial greenhouse using RO, treat brine as a regulated waste stream:

- Improve recovery first: Work with your RO supplier to push recovery higher (50–70% where feed quality allows) so you create less brine per m³ of permeate, in line with efficiency targets similar to those considered in Sri Lanka’s RO performance studies here.

- Segregate brine: Run brine to a dedicated tank, not mixed with nutrient waste.

- Use strategic reuse where acceptable:

- Blending small fractions into irrigation for salt-tolerant non-food landscaping, away from shallow wells.

- Evaporation pans or lined solar ponds in arid regions, with CEA/local authority awareness.

- Get clearance from CEA/local authority for any discharge into public drains, canals or water bodies. Provide TDS/chloride data and estimated volumes.

Non-negotiable: do not discharge RO brine directly into paddy fields, small tanks or unlined drains that feed them. Salinity damage will travel with return flows and quickly become a community issue.

3.5 Dial the hydroponic system to the water, not the other way around

Once your intake and treatment are sorted, you still need to run the system according to your water realities.

Kratky systems (jars, tubs, channels):

- Use storage-stable nutrient solutions with reasonably low starting EC (1.2–1.4 mS/cm for leafy crops).

- If alkalinity is moderate, add nitric or phosphoric acid at makeup to bring pH to 5.8–6.0 and expect a slow upward drift over the crop cycle.

- Design reservoir sizes so that you do not have to top up with raw PDN water mid-cycle; top-ups should be nutrient solution or pre-adjusted water only.

DWC systems (raft beds, buckets):

- Install reliable aeration on all beds; PDN stability does not make up for low dissolved oxygen.

- Monitor EC and pH at least once per day in commercial setups. Use PDN/RO blend as makeup water and adjust pH with acid/alkali.

- Plan partial solution changes based on salt accumulation, not calendar weeks. If top-up volumes equal your original tank volume and EC is creeping up, it is time to dump or reuse on field crops.

NFT / drip greenhouse systems:

- Fit inline EC and pH sensors if budget allows. Stable PDN lets you run tighter control loops.

- Use closed or semi-closed recirculation with careful monitoring rather than full drain-to-waste. That is how you prove low m³/kg water use if questioned by authorities or lenders.

4. What to watch long-term to stay drought-proof and compliant

4.1 Monitor and document water use

The more PDN systems expand under ADB and government programs, the more scrutiny big water users will face. Turn that into an advantage by building your own dataset:

- Install meters on PDN intake and on key sublines (for example greenhouse block, nursery, fogging/cooling).

- Track m³ of water per kilogram of saleable output by crop. That is your best defence if others accuse CEA operations of “wasting” water.

- Share headline numbers when negotiating allocations or expansion with Irrigation Department or NWSDB officers.

4.2 Watch EC, hardness and alkalinity trends across seasons

PDN supplies often blend reservoir, river and groundwater sources that shift across dry and wet seasons. At least quarterly, test:

- Feed water EC.

- Total hardness.

- Alkalinity.

If you see trends (for example alkalinity climbing each dry season), adjust your RO blend ratios and acid dose, not just your nutrient recipe. Keeping tight control over these three parameters will prevent most hidden stress in Kratky and DWC.

4.3 Keep RO and waste management under active review

Brine and sludge handling is unlikely to get looser as Sri Lanka tightens water governance and environmental enforcement. To stay ahead of rules on RO brine disposal:

- Log brine volumes and approximate TDS.

- Store permits, clearances and correspondence with CEA and local authorities in a simple compliance file.

- Periodically explore salt-tolerant reuse options or technological upgrades (for example higher-recovery membranes, blending strategies, alternative softening) so you are not locked into one waste-heavy configuration.

4.4 Design expansions around water, not the other way around

When PDN access improves, it is tempting to double your greenhouse area overnight. The smarter approach is to:

- Upgrade buffer storage, filtration and RO first so they can handle higher flows.

- Confirm with your supplying agency (Irrigation Department or NWSDB) that additional demand is compatible with basin plans and any ADB project covenants.

- Expand in phases, monitoring how EC, pressure and availability hold up during the next dry season.

4.5 Practical drought-proofing checklist for Sri Lankan CEA sites

Use this as a quick audit against your current or planned build:

- PDN intake has meter, isolation valve, pressure control and written approval.

- Covered buffer tank sized for at least 1–2 days of peak greenhouse demand.

- Filtration chain sized to handle expected turbidity and any residual chlorine.

- Water quality baseline: EC, pH, hardness, alkalinity tested and logged.

- If RO is installed: recovery optimised, brine tank in place, disposal plan agreed with local authority/CEA.

- Hydroponic systems (Kratky, DWC, NFT, drip) tuned for your final blended water profile.

- Water use per kg output tracked and reviewed every season.

Do that, and Sri Lanka’s new irrigation and PDN investments stop being just “more water”. They become the backbone of a resilient, compliant hydroponic and greenhouse operation that keeps producing when surface canals run low.

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.